Reading: Moses 8:19-30; Genesis 6:5-22; 7:1-10

Since I first wrote this four years ago, it has been one of the most-popular, most-read posts, and one I refer people to often, because it was where I laid out my longest argument introducing people to the idea of genre in scripture.

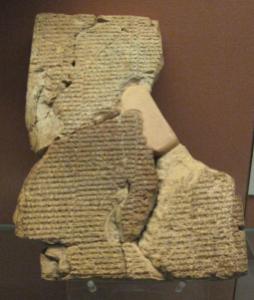

Atrahasis, an ancient mesopotamian creation and flood story.

I am an Amazon affiliate, and purchases made through the Amazon links below may grant me a small percentage.

Since then, I’ve also talked about it in two podcasts with LDS perspectives (here on the Bible in general and here more specifically on Genesis 1); I also spoke about it at length at BYU’s Sperry Symposium in October, which you can watch here.

Let’s begin with some big picture ideas that apply all over scripture. I substituted in our Gospel Doctrine class last week, and opened by asking, “Is Much Ado About Nothing literal or figurative? If you’re not familiar with Shakespeare’s comedic play, the 1993 adaption with Emma Thompson, Kenneth Branagh, Denzel Washington and Keanu Reeves, or the recent one by Josh Whedon, feel free to substitute either Bambi or The Bourne Identity.

Literal or figurative?”

Someone slowly offered, “…well, it’s fiction.” And this was kind of the point. Before answering a forced and simplistic dichotomy, they realized that the question didn’t really apply because of the genre of the material in question. We didn’t pursue this much in class, but I used it to illustrate that oftentimes when reading scripture, we assume that our two options are

- “literal” (by which people seem to mean “historical” or “actually happened”)

- “figurative” (which should mean “symbolic” or “metaphorical” but who knows what people mean)

As made obvious when applying this dichotomy to modern genres that we’re more familiar with, these binary categories and the usual questions that go along with them are really inadequate. Jason Bourne doesn’t stand for anything but Jason Bourne, but ruling out a “figurative”or “metaphorical” interpretation obviously doesn’t mean The Bourne Identity is a “literal” or historical account. Jason Bourne is a “literal” movie, but that doesn’t mean it is “real” or it actually happened. Similarly, the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland is a literal cat, but “literal” and “real” or “actual” are not synonyms.

You cannot put good questions and expect fruitful answers from a text apart from a grasp of the kind of material it is in the first place; misjudge the genre, and you may skew many of the things you try to do with the text.

So says Walter Moberly in an excellent overview of how to read Genesis 1-11. In other words, knowledge of what kind of thing the text is, tells us the kinds of questions we should be asking; It is appropriate to ask historical questions of genres that make historical claims, like documentaries and “based on a true story” films like Selma. It’s misguided to ask historical questions about Star Wars, because of the non-historical genre of film. Someone not familiar with the genre might say, “But it claims to be historical! It says it happened a long time ago, in a galaxy far far away! That a historical claim!” It can be easy to misread genres we’re not familiar with, and this happens often, especially with ancient scripture.

Typically in our classes, we begin with an unstated assumption that whatever part of the Old Testament we’re reading must be of a historical genre (because it’s scripture, and scripture is “true” and “true” is usually a synonym for “historical” in LDS usage) and then set about asking all kinds of questions about the logistics of how it was done, whether it was local or global (more on that in a minute), or it becomes a point of contention between “believers” and “doubters,” “science vs religion” or “conservatives vs. liberals.”

Mixing up genres is called genre confusion, which I’ve talked about before, with Jonah and in my podcast on genre.

So what is the flood account, then? To begin to answer that question, we need to know that the Genesis flood account is one of several ancient Near Eastern flood accounts, and it resembles them greatly. (Here is an introductory Institute handout about these other major stories.) In fact, those resemblances —combined with German Protestant assumptions and anti-Semitic bias at the time they were discovered and translated in the late 19th century— led to conclusions that the Genesis flood was a simplistic rip-off of these other Mesopotamian accounts. Scholarship has become much more nuanced since then, but Peter Enns pointedly asks a still-relevant question.

The problem raised by these Akkadian [flood and creation] texts is whether the biblical stories are historical: how can we say logically that the biblical stories are true and the Akkadian stories are false when they both look so very much alike? (Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament, 41.)

Here again, we have to recognize that simple dichotomies like “true” and “false” fail to account for the complexity of scripture and life.

My summary position is that the Genesis account is both an adaption of and a reaction against other ancient Near Eastern flood stories, much as creation in Genesis 1 is both an Israelite adaptation and polemic reaction against other ancient Near Eastern creation accounts.

Very briefly, I think there may be a historical kernel, a memory of a flood behind the current text (there are regular river floods both in Mesopotamia and Egypt.) However, as it currently stands in the text, the flood tradition has been pressed into use and expanded (for polemical anti-Mesopotamian purposes?) into a universal cosmological flood. The flood is a reverse creation, undoing Genesis 1 by erasing order and structure, and returning the world to its pre-creation watery/chaotic state (as in Gen. 1:2, the tehom or watery Deep from which everything was created. See here and here for a long explanation.) Then the waters recede, and Noah is a new Adam in the new creation.

This is tied very closely to the Priestly creation account of Gen 1-2:4a and its ancient cosmology. Note I said universal/cosmological, not global. Neither the Israelites nor their ancient neighbors conceived of the world as a globe circling the sun; rather, the earth was a flat, relatively small land surrounded by water on all sides, with water beneath and above, restrained only by the solid dome of the firmament, which was supported by the mountains at the ends of the earth, including the mountain range of Ararat.

This is the cosmology, or view of the universe, assumed and made explicit in Genesis 1, which “literalists” must take pains to rationalize away. The flood account envisions the ark bumping up against the mountainous sides and nearly the ceiling (firmament) of creation, as the cosmic waters fill to the brim, and then recede. Creation and its subsequent pollution (see the article by Frymer-Kremsky below for more on this term) are thus wiped away, resulting in a new creation with Noah as the new Adam. While it is a universal or cosmological flood, it is not necessarily a historical flood.

While the manual wisely avoids nearly every historical question to focus on application, it’s inevitable that someone somewhere is going to make traditional claims on this topic. Let’s briefly address a few questions of the flood, frustrated once again at how little we can really do here. (I have a pipe dream of turning my not-yet-finished-but-somehow-wildly-successful-in-my-mind book into a trilogy, with the second volume on the flood in Genesis 6-9, and the third on Genesis 2-3. As it turns out, John Walton is already doing this for an Evangelical audience, and I recommend his books. )

First, we should note the views of someone like Elder John Widtsoe, who, as a scientist, struggled with the idea of the flood. He tentatively proposed that it simply rained everywhere simultaneously, so the world was covered in a minuscule layer of water for a millisecond. In doing so, he offered several wise observations about reading scripture.

First, we should note the views of someone like Elder John Widtsoe, who, as a scientist, struggled with the idea of the flood. He tentatively proposed that it simply rained everywhere simultaneously, so the world was covered in a minuscule layer of water for a millisecond. In doing so, he offered several wise observations about reading scripture.

We set up assumptions, based upon our best knowledge, but can go no further…. Many Bible accounts that trouble the inexperienced reader become clear and acceptable if the essential meaning of the story is sought out. To read the Bible fairly, it must be read as President Brigham Young suggested: ‘Do you read the scriptures, my brethren and sisters, as though you were writing them a thousand, two thousand, or five thousand years ago? Do you read them as though you stood in the place of the men who wrote them?’ (Discourses of Brigham Young, p. 197-8). This is our guide. The scriptures must be read intelligently.- Evidences and Reconciliations, around p.126.

I would point out that our best knowledge of this topic, who wrote the scriptures, when, and why, has increased significantly since Widtsoe penned that statement.

Second, in case you’ve never seen the scientific arguments (i.e. the problems raised by reading Genesis 6-9 strictly as a history), it is flatly impossible that there was a global flood that covered the highest mountains and left no trace at all, unless God is a trickster of some kind who insisted on removing all evidence. I believe in a deity who does have the power to unleash a worldwide flood (and it would take supernatural physics to produce that much water), but not a god who would then hide all evidence of such a massive worldwide geological miracle. It should have left all kinds of evidence all over the world, but there simply isn’t any. By contrast, what kind of evidence would something like the Resurrection leave? I’m fine with God doing unscientific things; I’m not fine with God not leaving any evidence for them, especially when that evidence should be absolutely massive.

In any case, it’s not necessary to attribute all arguments against a historical worldwide flood to disbelief or “the world” (guilt by association?) since the Bible itself is not consistent on the topic. I think two things are clear.

- The Biblical text in Genesis 6-9 depicts a universal flood.

- Whether this is because it was a universal flood or because it only appeared universal from the perspective of the ark’s occupants is a traditional side argument. (I ask, if it’s a “local” flood, why the need to preserve all the animals on the ark?) The cosmology of the text, its connections to Genesis 1, and the details make it a universal, cosmological flood. This does not necessarily make it a historical flood.

- The Biblical text elsewhere knows nothing little about a universal flood and seems to assume it didn’t happen.

- Genesis 4:20-22 tell us of “Jabal; he was the ancestor of those who live in tents and have livestock.His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the ancestor of all those who play the lyre and pipe.[And] Tubal-cain, who made all kinds of bronze and iron tools.” (NRSV) The post-flood author seems to assume that the descendants of each of these three still exist in semi-distinct groups. Weren’t they all killed off in the flood?

- Genesis 6:4 tells us of “giants” or nephilim, pronounced nuh-fill-eeym, accent on last syllable (no relation to Nephi. The root of nephilim is NPL, the root of Nephi is NPW or NPY); “The Nephilim were on the earth in those days [before the flood]– and also afterward“! (NRSV, emphasis added.) The Nephilim are around before and after the flood text. Numbers 13:33 tells us that the Anakites are their descendants. If we’re talking about a historical, universal flood, why weren’t they all killed off? How can they have descendants? One Jewish tradition maintains that one of them held on to outside of the ark, and survived that way.

Any [interpretive] solution must take the text seriously, yet be willing to see the text in ways that the original author and audience may have seen it. It likewise needs to take logistical problems seriously. It is a weak interpretation that has to invent all sorts of miracles that the text says nothing about in order to compensate for the logistical problems.

My final advice is, stick with the manual and the ideas it teaches, as summarized by the Jewish Study Bible, that “the ark symbolizes the tender mercies and protective grace with which God envelopes the righteous even in the harshest circumstances.”

Further Reading from me:

- The difficulties of history-writing, from The Ensign.

- Does the Book of Ether “confirm” the flood? No, it seems to refer to of creation out of water, as Genesis 1 has it. Can we take modern, Mormon scripture as simply being facts about history and science, including the flood and creation of the earth? I don’t think so. See this post and especially my FAIR Conference talk about the nature of scripture, revelation, and interpreting Genesis.

- There was an Ensign article on the flood and Tower of Babel in 1998. It has many problems, but the biggest one is the assumption of “modern historical narrative” for the genre of Genesis 6-9. I responded to it here.

Further reading elsewhere

- Tikva Frymer-Kremsky “The Atrahasis Epic and Its Significance in Understanding Genesis 1-9” Biblical Archaeologist 40. PDF link.

- “Flood” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch. PDF Link.

- I think pointing out scientific problems is not the best way to convince people that there is a better way to read the text; this post discusses such an article that lays out the vast amounts of evidence against a worldwide flood in the last few thousand years.

- Keepapitchinin looks at how this lesson was taught in the 1930s.

- Was Noah’s flood the baptism of the earth? This article from BYU’s religious studies center argues against the idea.

- I like Peer Enns’ take on the flood story, and the problems of simplifying it and teaching it to children.

Tidbits:

- Repenting– In the KJV, it “repenteth God” that he created mankind, but the Book of Moses changes it to avoid the idea of God needing to repent. (See similarly my treatment of the problem of God committing “evil” in Amos, according to the KJV.) In the KJV, while “repent” sometimes carries our modern idea of “turning away from sin and repenting” it more often means “to have remorse, feel bad” (Hebrew nicham) and clearly, that is God’s feeling about creation when he sees its corruption (a leitmotif in the Hebrew), leading to the cleansing flood.

In Moses, it is Noah who repents. This is actually a little puzzling, because it implies that God kills everyone and everything due to a) Noah’s feelings about creation and b) threats on Noah’s life.“And it repented Noah, and his heart was pained that the Lord had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at the heart. And the Lord said: I will destroy man whom I have created, from the face of the earth, both man and beast, and the creeping things, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth Noah that I have created them, and that I have made them; and he hath called upon me; for they have sought his life.”

Is the entire population of the world really contingent on Noah’s feeling threatened and rejected? Or is that making the wrong kind of assumptions about the text? How else can this passage be read? See my post here for textual comparison.

- Noah and preaching- We often imagine Noah being mocked for building a boat, and preaching for as many people as possible to repent and join him on the boat.

“We can easily imagine that Noah was involved all of his life in trying to make an impact on his world for righteousness. Usually the tradition today, however, implies that Noah was trying to persuade them to join him in the ark and gain deliverance. The evidence of the text argues against that possibility. Noah was told exactly whom to bring into the ark, and space was made for these eight passengers. Even if others wanted to gain sanctuary in the ark, it is not a given that such an option was available to them.It is interesting to compare the mentality reflected in Gilgamesh on this issue. There it is assumed that if the general population were told that a flood was coming, they would all readily believe and want to be delivered. In the Mesopotamian versions, since no humans were supposed to be saved at all, widespread alarm would have been disastrous. Consequently, Utnapishtim and his god, Ea, have to devise a half-truth to deceive the population of Shuruppak so that they will not become suspicious of the building activity. They contrive a story that Utnapishtim is out of favor with Enlil, so he must build a boat to go to the great sea to live with Ea, his patron god, lest his presence bring Enlil’s wrath on the city.

“Ea opened his mouth to speak, saying to me, his servant, “Also you will say to them this: ‘For sure the god Enlil feels for me hatred. In your city I can live no longer, I can tread no longer [on] Enlil’s ground. I must go to the Ocean Below, to live with Ea, my master, and he will send you rain of plenty.” Certainly we would not attribute such deception to Noah, but this section illustrates well how different the ancient world was from our modern thinking. Skepticism about the punitive intentions of the gods was far more rare in the ancient world than it is today. People back then would have found it intrinsically credible that deity would send a flood to wipe out life. It is far more likely that people would have clamored to get on board than that they would ridicule Noah for his undertaking.“– Walton, Genesis, 317-18. Emphasis mine.

- Baptism of the earth– This idea can’t be used to argue for a universal historical flood. The idea of the earth being baptized comes *from* the idea of a global flood, it was an interpretation of a worldwide flood. To then turn it around and use baptism of the earth as an argument *for* a global flood is circular and gets the causality backwards. But lets ask a different question- Why does the planet need baptism? Do dogs? Plants? Can it make decisions, or repent? Did someone lay hands on it? What sins had it committed? Is it now a member of the church? Again, the idea of the earth’s baptism grew out of the reading of a global historical flood, not revelation, and consequently it’s not a strong argument for a worldwide flood because of that circularity. See the article here.

- Ages and long life– The ages of Adam, Noah, and other early figures are often compared to the Sumerian King List (wikipedia, text in translation here), which as you might imagine is a list of the reigns of various Sumerian kings. Many of these kings reign for extremely long and detailed number of years. They’re not round numbers, but very detailed, upwards of 30,000 years in some cases. In yet another point of contact between Genesis 1-11 and Mesopotamia, “the ages of the Mesopotamian antediluvians in the Sumerian King List are given in multiples of 602 years and those of the Bible in Genesis 5 are given in multiples of 60 months with the occasional supplement of 7 years.” (Anchor Bible Dictionary, “Noah’s Ark.”) Mesopotamia did not use a base-10 system, and the Biblical ages generally follow a Mesopotamian pattern. Kenton Sparks points out a generall pattern between the flood and the ages of people before and after in an excellent little book, “These postdiluvian kings [in the Sumerian Kinglist] reigned for fewer years than their pre-flood predecessors — just hundreds of years instead of millennia. This pattern of very-long-lived kings, followed by a flood, then long-lived kings is akin to the pattern in Gen 1 – 11, where very-long-lived patriarchs (Gen 5) are succeeded by a flood and then by long-lived patriarchs (Gen 11). This shows that the structure of Gen 1 – 11 has a long pedigree stretching back to the early second millennium BC.” Elsewhere, Sparks argues that the authors of Genesis modified the geneaologies and ages they include to emulate Mesopotamian patterns, which explains their oddness. In other words, once again, Genesis is not trying to convey strictly historical information, and reading it as if it is doing so… is misreading it.

Whoo. That’s a lot of material 🙂

As always, you can help me pay my tuition here via GoFundMe. *I am an Amazon Affiliate, and may receive a small percentage of purchases made through Amazon links on this page. You can get updates by email whenever a post goes up (subscription box below) and can also follow Benjamin the Scribe on Facebook.

February 4, 2014 at 10:10 pm

Thank you for this post. I linked to it from my blog. http://loveliestyear.blogspot.com/2014/02/sunday-school-class-and-not-reading.html?showComment=1391569577271#c1012423784020787478

February 5, 2014 at 10:39 am

Genevieve, there’s an interesting tidbit about the Ensign article you refer to in your post. CES (now known as S/I) has a list of references and articles for Seminary/Institute lessons. That Ensign article is conspicuously absent from the lesson on the Flood. I think (hope) that is significant.

February 5, 2014 at 3:46 pm

I hope so too.

February 5, 2014 at 1:25 pm

Thanks for a great post, Ben. I have a friend who will really appreciate seeing this. I have clicked on some of the links you provided, although not all. Do we have any idea who the author of the Genesis account is? Also, do you have any thoughts about what the author might have been claiming about his god in responding to other flood accounts? Some of the information in the links emphasizes the flood in response to wickedness, but was punishment the primary message? That answer may be longer than lends itself to a comment, and if so, no worries.

Thanks again!

February 5, 2014 at 2:00 pm

Current scholarship splits up the flood account into two, J (the author of the second creation account in Genesis 2:4 onwards) and P (the author of Genesis 1). “Author” probably isn’t the correct term, as we’re not positing individuals per se. The idea is that there were two Israelite traditions, woven together by an editor. So instead of having P then J (like we do with Genesis 1, then 2:4) we have P1,J1,P2,J2,P3,J3.

I don’t entirely accept that we can perform this kind of minute surgery on individual verses, but it does account for internal contradictions. P (being priestly, held that there was no sacrifice until the priests) only has animals going in pairs. J, however, accounts for Noah offering sacrifice after, and thus specifies 7 pairs of clean (i.e. sacrificial) animals and 1 pair of unclean animals were taken on the ark (Genesis 7:2).

See here for what they look like separated. http://imp.lss.wisc.edu/~rltroxel/Intro/flood.htm

In counterpoint, the strongest resemblances to other ancient Near Eastern flood texts only occur in the combined text, not the separated stories. Quoting Walton again, “This consensus began to crumble when critical scholars who asserted that the Genesis account derived secondarily from ancient Near Eastern literature noticed that both J and P would have derived part of their information from the Mesopotamian sources, but in other places deviated from those sources. In effect, then, the parallels between Genesis and the epics of Gilgamesh and Atrahasis argued for the unity of the Flood narrative instead of dividing it between sources. As Wenham comments, “It is … strange that both J and P versions should lack features of the common tradition, but when combined create an account which resembles it.”

So the short answer is, I don’t know who the author is.

The comparison is probably similar to Genesis though, in which deity cares about humanity and creation. The other flood accounts, humans are an annoyance preventing a deity’s sleep and therefore deserving of death.

Also, the flood isn’t about punishment at all really, but cleansing. I hinted at this, but didn’t get into it much. English misses it because of translation issues, but the idea is that sin and corruption (the leitmotif) cause pollution. “All flesh” had become corrupt and polluted, filling the earth with violence. Consequently, there was nothing left to do but figuratively sweep everything off the table and begin again with a clean slate. There’s little implication of punishment, much more of crumpling up a piece of paper and taking a new clean one. Frymer-Kremsky talks about this a good bit, I believe.

February 5, 2014 at 2:32 pm

This is really helpful and also motivates me to study more. Thanks!

February 7, 2014 at 9:06 am

What kind of lights did Noah use on the ark?

…

…

…

…flood lights…of course.

May 21, 2015 at 4:02 pm

Thanks, Ben. This is extremely helpful. Applications for these insights spread out in all directions.